When he stood with his camera in his hand on the scaffolding in the middle of Hendrik van Viandenstraat in 1978, Arne Haytsma could not have imagined the photos he would take in Amersfoort at that time would continue to be taken all over the world for decades to come.

Downstairs, in the street, Jan Wittenberg was walking up and down with a megaphone in his hand. ‘I had to direct everything. I believe we chased the cars away all afternoon: ‘because of filming!’. Only an empty street was usable. On either side of the street there were two policemen to stop the traffic. The whole neighborhood had walked out and was watching. But of course the street had to remain empty. For the statue I had to send the people back each time. That didn’t quite work out. You see people in the porches. And in the picture with the pedestrians there are too many. It just couldn’t be stopped.’

In the meantime, 40 cars were waiting in the side streets for their photo opportunity: the use of space of the car. Remarkably many Renault 4’s and Deux Chevaux’s. ‘The cars were the most difficult. Not many people in our circle of acquaintances had a car’, says Haytsma. ‘That’s why you see so many of these beginner cars. But there is also a Snoek (the DS, the then top model of Citroen, ed.). It belonged to my neighbor.’

The names Daan van Tol and Arne Haytsma are in the photographs, but Haytsma emphasizes that Wittenberg – in 1975 one of the founders and the first president of the First Real Dutch Cycling Federation (ENWB) – was the undisputed driving force. ‘At that time I worked for the Werkgroep 2000,” says Haytsma. ‘And we met in the kitchen where we discussed the use of space.’

Futurology

As Haytsma explains, the Werkgroep 2000 foundation was concerned with ‘futurology’. When Haytsma worked there, the emphasis was on the democratization of spatial planning. In practice, this meant organizing participation in construction and traffic plans. One of the future projects was about transport: ‘Wijs op Weg’. It was a time of drastic breakthroughs in cities for the car. Did that really have to happen? Couldn’t it be otherwise?

The NS (Dutch Railways, red.), which lost passengers to the car, decided to call in the Werkgroep 2000. ‘We received a substantial budget for this from the NS. The NS wanted to initiate a social debate about transport and the organization of space. The Werkgroep 2000 felt that slow traffic – cyclists and pedestrians – should be supported.’

The Real Dutch Cyclists' Union (ENFB)

At the time of the poster, following complaints from the ANWB, the ENWB was renamed the Real Dutch Cyclists’ Union (ENFB) and held office in the old villa of the Werkgroep 2000 in Amersfoort. First in the front room and later in the bathroom’, remembers Wittenberg. What the united cycling activists wanted fitted in well with the approach of the Werkgroep 2000. ‘They were working on the professionalization of participation procedures,’ says Wittenberg. And of course the cyclists also wanted to be heard. Wittenberg (then a student of urban planning) was concerned with the ‘democratization of decision-making’. ‘For me, urban planning is a profession which, through analysis and design, seeks solutions to people’s contradictory wishes and opinions about the use of space. But during consultation meetings we found out that urban planning issues were too abstract for many people.’

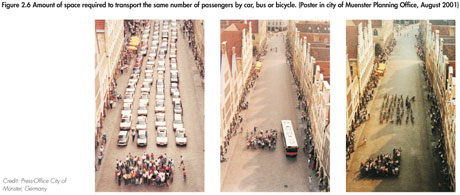

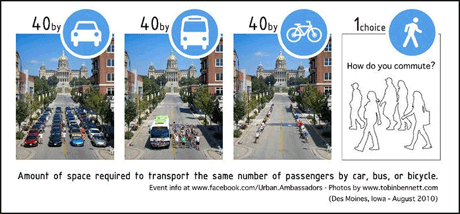

While the question Wittenberg wanted to ask is actually quite simple: whose space does it belong to? ‘The photographs we took represent that question. The poster was meant to help people clarify that question themselves. ‘I think that one poster says more than 1000 pages of text.’ How he got on it, he doesn’t remember. “That just comes to the surface.’

Copied Worldwide

In several countries, based on Wittenberg’s idea, similar photos have been taken to make it clear that the car requires a lot of space. And with that, the poster is perhaps the most influential publication of the Dutch Cyclists’ Union ever.

At the time itself, the scope of the photos was not yet so clear. On the contrary. From Jan Ploeger, who was a student of Civil Engineering at the time and was active within the Cyclists’ Union, I receive scanned reports of the editorial meetings. It was with him that my search for the genesis of the poster began.

What did people think of it then? The six photos were a bit too much, was the verdict in the editorial meeting. With four it could also have been fine. Fortunately, the poster turned out to have eight photos. The publication in the ‘Vogelvrije Fietser’ was the beginning, then came the poster.

The Car Was Chopping Down So Much Space

According to Ploeger, it’s not surprising that the idea for the poster originated at this time: There were very creative people active at that time. We were looking for ways to reduce the size of the car. It was very massive; the car was chopping down so much space.’

To get the message across, Ploeger says, all sorts of experts were called in, including advertising man Hans Ferrée, the creator of the name ‘Ugly Duck’. He said: ‘You have people who are still cycling and you have people who are going to cycle again. He had seen that very well.’

Ploeger stopped volunteering for the ENFB when he had to graduate. During his career, he spent a lot of time on bicycle policy. And now, after his retirement, he is doing PhD research at Eindhoven University of Technology into the history of the bicycle and train combination as an alternative to the car.

That fits perfectly with the early days of the Cyclists’ Union. The activists weren’t just about the bicycle. In reducing the car and reclaiming space, public transport was just as important. Also for Wittenberg, the man with the megaphone in the Hendrik van Viandenstraat. Just like Ploeger, he also had to stop to graduate. The booklet he wrote with his graduation – the road to the station, design ideas for slow traffic routes – was published in 1980, with the support of the NS (Dutch Railways).

How Does Hendrik Van Viandenstraat Look Now?

How does he now look back on what has been achieved, is the public space well used? He sighs for a moment to indicate that this is a question you can’t answer quickly. But he can say two things. The first is that the role of public transport – also prominently present on the poster – disappoints him. ‘The Netherlands has a half-baked public transport. If you have a very strong public transport network, it structures the spatial planning of our country and our cities. But that hasn’t happened. Instead, we have had an endless diarrhea of suburbs.’ In practice, most suburbs are mainly built on good car accessibility.

But with many stations it turned out well, says Wittenberg. ‘It’s not for couples now, but stations were boring places with one entrance. Now you see that back entrances have been made. The stations are now embedded in the urban environment with stores, parking spaces and all kinds of other facilities.’

And how did it end with the Hendrik van Viandenstraat where it all began? How was the space divided up there? Wittenberg mails a photo from Google Streetview after the phone call: ‘After 42 years, the street still offers a sad sight with a patch of asphalt 10 meters wide without adequate bicycle facilities.’ The question ‘Whose space?’ is as topical as it was in 1978.

The article was written by Michiel Slütter

Translation: Chris Bruntlett